According to Braithwaite (2004), restorative justice is:…a process where all stakeholders affected by an injustice have an opportunity to discuss how they have been affected by the injustice and to decide what should be done to repair the harm. With crime, restorative justice is about the idea that because crime hurts, justice should heal.

Introduction

According to Braithwaite (2004), restorative justice is:

…a process where all stakeholders affected by an injustice have an opportunity to discuss how they have been affected by the injustice and to decide what should be done to repair the harm. With crime, restorative justice is about the idea that because crime hurts, justice should heal.

Restorative justice can be seen as a subset of restorative practice, which offers a common thread to tie together theory, research and practice in diverse fields such as education, counselling, criminal justice, social work and organisational management. The fundamental premise of restorative practice is that people are happier, more cooperative and productive, and more likely to make positive changes when those in positions of authority do things with them, rather than to them or for them.

The use of restorative practices can:

- reduce crime, violence and bullying

- improve human behaviour

- strengthen civil society

- provide effective leadership; and

- restore relationships

While restorative practices have been widely used in youth justice and education settings to repair harm, there is a great deal of debate about its suitability in cases of family violence. Chief among the criticism is that when applied to intimate partner violence, these informal practices can fail to protect the safety of survivors or lead to re‑victimisation. It is also argued that restorative practice may minimise the harm done to women or appear too lenient in the punishment of perpetrators. However, other commentators have made opposing arguments, seeing restorative practice as offering a better way to seek safety and accountability than the current legal system. Pennell and Burford (1995), for example, contend that family group conferencing offers a way to expand a coordinated community response to stopping violence against women and their children, recognising that family violence cannot be stopped without the concerted and cooperative effort of families, communities, and state institutions.

In November 2015, Relationships Australia’s online survey sought further understanding of the community’s views on the applicability of restorative practices to family violence by posing a few questions to visitors to our website.

Previous research finds that…

- Around one in five Australian women and one in twenty Australian men have experienced violence at the hands of an intimate partner (ABS, 2013).

- Between 2005 and 2012 there was no statistically significant change in the proportion of women and men who reported experiencing partner violence (ABS, 2013).

- In New Zealand, family group conferences for youth were legislatively established by the Children, Young People, and Their Families Act more than three decades ago.

- Restorative justice has been found to reduce the rate of reoffending, increase victim satisfaction, and saved government and community resources.

Survey Results Analysis

More than 1900 people responded to the Relationships Australia online survey in November. Around four‑fifths of survey respondents (80%) identified as female.

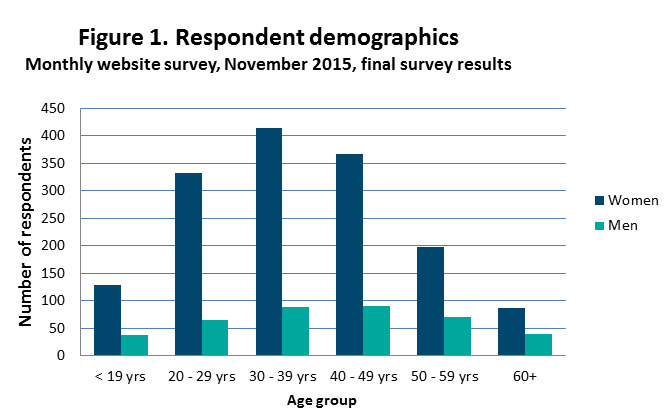

As was the case for last month’s survey, more females than males responded in every age group (figure 1). More than ninety per cent (92%) of survey respondents were aged between 20‑59 years, with the highest number of responses collected for women aged between 30-39 years (inclusive).

The demographic profile of survey respondents remains consistent with our experience of the people that would be accessing the Relationships Australia website.

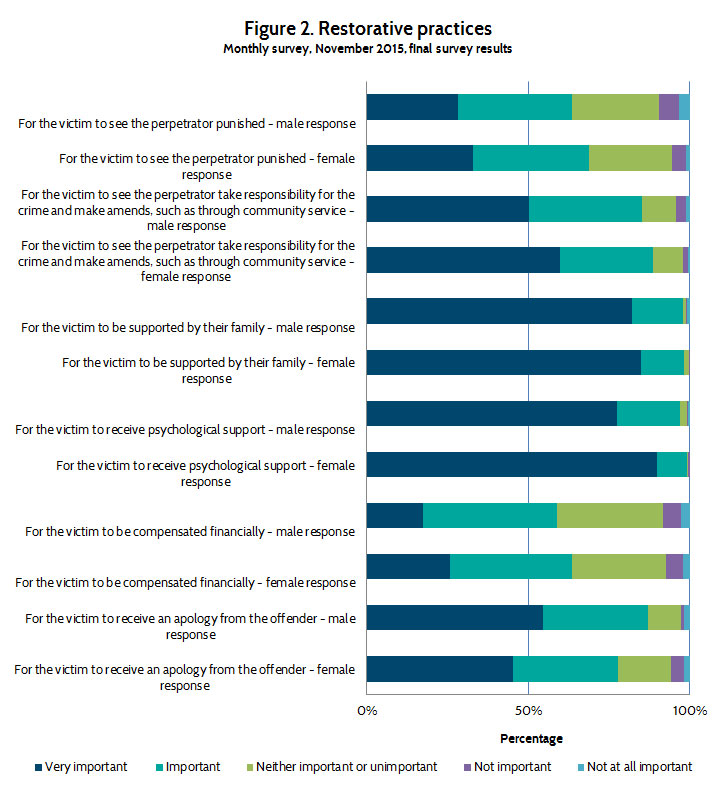

When asked about the importance of a range of factors to the needs of victims of family violence, both male and female respondents to November’s monthly online survey assigned high levels of importance to all categories identified by the questions. However, overall, respondents were more likely to report that family and psychological support were more important to meeting the needs of victims of family violence than the perpetrator making amends for the crime or being punished, the perpetrator apologising to the victim or financial compensation.

Female respondents were more likely than male respondents to report that it was important or very important for a victim of family violence to see the perpetrator punished (69% compared with 63%) or take responsibility for the crime and make amends (89% compared with 85%). Almost all men and women reported that the support of family was important or very important in satisfying the victim’s needs, while women attached higher levels of importance to the victim receiving psychological support when compared to men (99% compared with 96%).

Around one-third of male and female survey respondents reported that they thought compensation was neither important nor unimportant, while a further two-thirds (Men 58%, women 64%) thought that compensation was important or very important in satisfying the victim’s needs. Eighty-six per cent of men and seventy-seven per cent of women thought that the victim receiving an apology from the perpetrator was important or very important in satisfying the victim’s needs.

References

Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2013). Personal Safety, Australia, 2012, Cat no. 4906.0. Canberra.

Braithwaite, John (2004). Restorative Justice and De-Professionalization. The Good Society 13 (1): 28–31.

Pennell, J. & Burford, G. (1994). Widening the circle: The family group decision making project. Journal of Child & Youth Care , 9 , 1-12.

Pennell, J. & Burford, G. (1995). Family group decision making: New roles for ‘old’ partners in resolving family violence: Implementation report (Vols. I-II). St. John’s, Newfoundland, Canada: Memorial University of Newfoundland, School of Social Work

Liebmann, M. Restorative Justice: How it Works, 2007, London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers

Wachtel, T. Defining Restorative”. International Institute for Restorative Practices. Retrieved 15 December 2015

Acknowledgement

Relationships Australia would like to acknowledge the assistance of the Regulatory Institutions Network, Australian National University, in developing this month’s survey questions.