Introduction

Would you like to be notified when a new survey report is released? Sign up here

Social identity theory was first developed by Tajfel and Turner in the 1970s. The theory proposes that part of a person’s concept of self, in other words a person’s sense of who they are, comes from the groups to which that person belongs. If a person belongs to groups that provide them with stability, meaning, purpose, and direction, then there will be an associated positive impact on their mental health (Haslam et al., 2016).

In this study, we measured neighbourhood identification, which reflects how much a person feels like they belong in their local community. People can belong to many groups, such as sporting teams, work teams, special interest, religious or community groups (Tajfel & Turner, 1979). However, people differ in how much they are committed to a group, in terms of their psychological and subjective sense of connection to it. When a group is particularly important and meaningful to a person, we say that it is part of their social identity (Postmes et. al., 2012).

This month’s online survey utilises five questions measuring psychological distress that are derived from the Distress Questionnaire-5, a short measure aimed at accurately identifying individuals who meet clinical criteria for a variety of common mental disorders, including: major depressive disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, social anxiety disorder, panic disorder, adult attention-deficit disorder, PTSD, and OCD (Batterham et. al., 2016). Social identification was measured with a single question ‘I identify with my neighbourhood’ (Postmes et. al., 2012).

Previous research finds that…

- shared social identity has a positive impact on work and life satisfaction because it serves as a basis for the receipt of effective support from ‘in group’ members (Cohen & Wills, 1985)

- a sense of shared identity allows for members of disadvantaged groups to work together to buffer themselves from the negative consequences of their circumstances (Schmitt & Branscombe, 2002)

- social identity loss (e.g. as a result of retirement, work restructuring, or illness) negatively impacts on mental well-being (e.g. Jetten, O’Brien, & Trindall, 2002)

- psychological interventions that target the development and maintenance of social group relationships to treat psychological distress arising from social isolation have been found to improve mental health, wellbeing and social connection (Haslam et. al., 2016)

Results

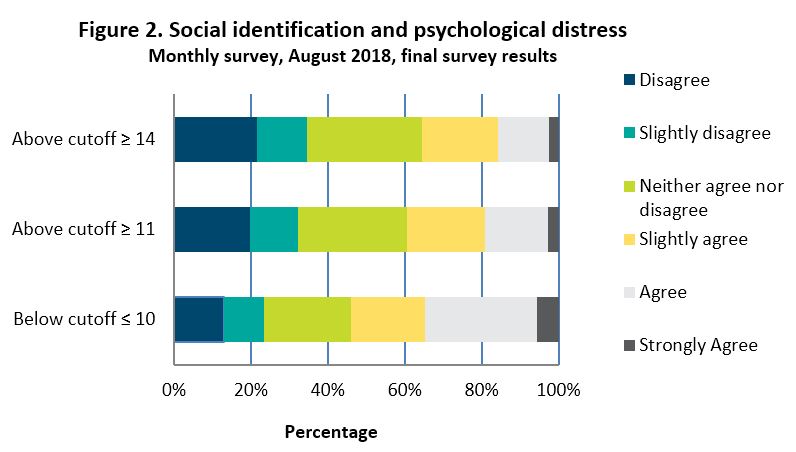

More than 1600 people responded to the Relationships Australia online survey in August 2018. Around three-quarters of survey respondents (77%) identified as female, with more females than males responding in every age group (figure 1). Eighty-four per cent of survey respondents were aged between 20 and 59 years, and more than 55 per cent of respondents comprised women aged between 20 and49 years (inclusive).

As for previous surveys, the demographic profile of survey respondents remains consistent with our experience of the groups of people that would be accessing the Relationships Australia website.

Total possible scores on the Distress Questionnaire scale range from 5 to 25, with higher scores indicating greater psychological distress. A cut point of ≥ 11 is used to screen for most common mental disorders, whereas a cut point of ≥ 14 is chosen for increased specificity in applications where a clinical case finding is required.

On average, survey respondents reported a score of 15.1. Women reported higher psychological distress on the Distress Questionnaire (15.2), when compared to the average score observed for men (14.7). Younger survey respondents were more likely to report higher distress scores when compared older survey respondents.

While women and young people also reported higher distress on the Distress Questionnaire in the study by Batterham and colleagues (2016), on average, monthly survey respondents reported significantly higher levels of distress across all categories of gender and age.

More than four-fifths (85%) of female survey respondents and four-fifths (80%) of men reported scores on the Distress Questionnaire above the specified score for screening for psychological distress. More than two-thirds (67%) of women and three-fifths (62%) of men reported scores above the specified cutoff score used to indicate clinical levels of distress (table 1).

Table 1. Psychological distress by gender, Number of

respondents above the Distress Questionnaire cutoff scores

|

|

Psychological distress |

|

|

Cutoff ≥ 11 |

Cutoff ≥ 14 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Female |

84.60 |

67.11 |

|

Male |

79.66 |

62.15 |

|

Total |

82.77 |

65.67 |

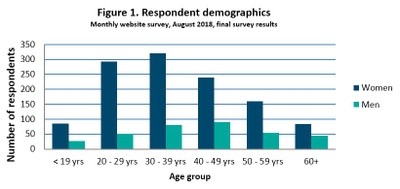

Psychological distress was associated with social identification (figure 2). Survey respondents who reported higher scores on the Distress Questionnaire were less likely to agree that they identified with their neighbourhood. One third (35%) of survey respondents reporting a score above the clinical cut-off score (≥14) and 32% of survey respondent reporting a score above the screening cut-off score (≥11) for psychological distress disagreed that they identified with their neighbourhood. This compares with 23% of survey respondents who did not report psychological distress.

References

Batterham, P,J, Sunderland, M, Carragher, N,, Calear, A,L, Mackinnon, A,J,, Slade, T. (2016). The Distress Questionnaire-5: Population screener for psychological distress was more accurate than the K6/K10. J Clin Epidemiol. 2016 Mar;71:35-42. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2015.10.005. Epub 2015 Oct.

Cohen, S., & Wills, T.A. (1985). Stress, social support and the buffering hypothesis. Psychological Bulletin, 98, 310–357.

Haslam, C., Cruwys, T., Haslam, A, Dingle, G., and Xue-Ling Chang, M. (2016). Groups 4 Health: Evidence that a social-identity intervention that builds and strengthens social group membership improves mental health. Journal of Affective Disorders, Volume 194, April 2016, Pages 188-195. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2016.01.010

Jetten, J., O’Brien, A., & Trindall, N. (2002). Changing identity: Predicting adjustment to organizational restructure as a function of subgroup and superordinate identification. British Journal of Social Psychology, 41, 281–297.

Postmes, T., Haslam, S., A, and Jans, L. A (2012) single-item measure of social identification: reliability, validity, and utility. Br J Soc Psychol. 2013 Dec;52(4):597-617. doi: 10.1111/bjso.12006. Epub 2012 Nov 4.

Schmitt, M.T., & Branscombe, N.R. (2002). The meaning and consequences of perceived discrimination in disadvantaged and privileged social groups. European Review of Social Psychology, 12, 167–199.

Tajfel, H., & Turner, J. C. (1979). An integrative theory of intergroup conflict. The social psychology of intergroup relations?, 33, 47.

Acknowledgement

We would like to acknowledge Dr Tegan Cruwys, Research School of Psychology, Australia National University, for assistance with the design of the August 2018 monthly survey. The data collected in this survey may be used by researchers from the Research School of Psychology to examine relationships between distress, neighbourhood identification and the characteristics of neighbourhoods.

Full-size image: 46.3 KB| ![]() View

View ![]() Download

Download